Opinion on Smart Lighting: “Creating truly smart cities: why interoperability and governance matter”

By Nicolas Keutgen, Chief Innovation Officer, Schréder

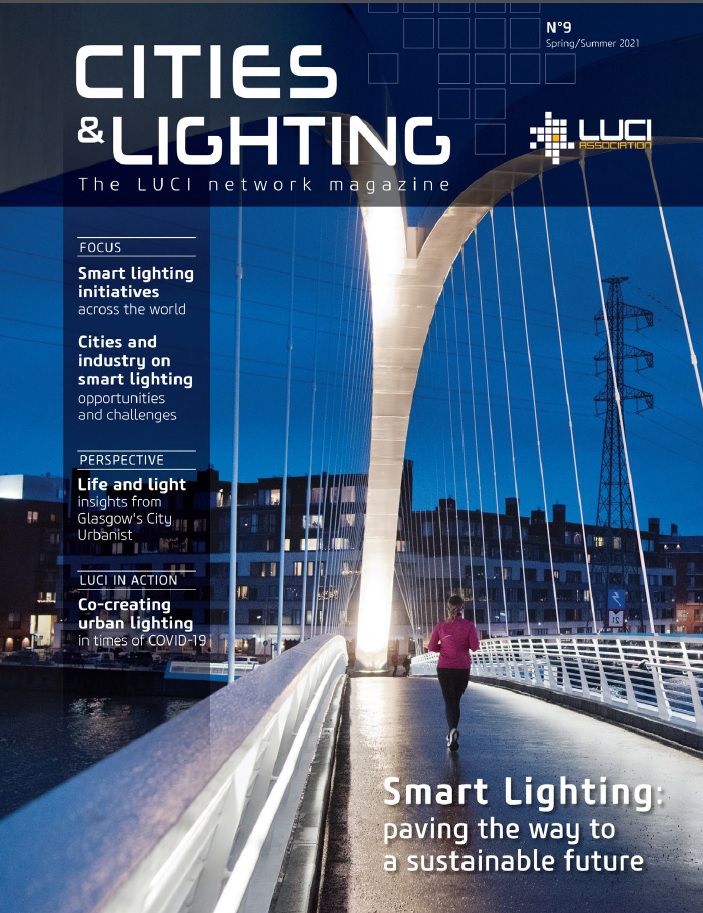

We asked leading city representatives and industry partners to share their views on opportunities and challenges regarding the next steps for smart lighting. They were published in the ninth issue of Cities & Lighting, out Spring 2021.

Many cities worldwide have already reduced their energy bills and carbon footprint by switching to LED technology. By integrating a control system to their network, they generate further energy-savings and deliver a better citizen-centric experience.

What appears to be a simple retrofitting operation can actually lay the foundation for a smart city. Indeed, smart street lighting enables cities to do much more than light – it can transform a lighting network into the backbone of a smart city platform. While remote management devices allow city managers to communicate with each light pole, setting dimming profiles, generating reports and managing tickets, certain control systems also enable street lights to seamlessly interact with sensors and actuators installed throughout public spaces. Consequently, cities should envision their Smart City when opting to add controls.

After analysing thousands of projects of different sizes (through our dedicated R&D centre, Schréder Hyperion), we identified two main challenges that cities face when developing a Smart City Vision based on existing lighting infrastructure.

The most pressing challenge is to push for the adoption of open and interoperable solutions amongst smart city suppliers and stakeholders. As the technological landscape continues to evolve, only the deployment of open solutions will solve existing and future needs. Interoperability will help prevent the so-called “vendor lock-in” trap that ultimately impedes the development of smart cities. Such a strategy will also facilitate a more open and competitive market, while encouraging common standards to be adopted across industries.

Secondly, the internal processes of cities are seldom set-up for transversal application management or data and infrastructure sharing. Indeed, as the light pole becomes the main host for multiple digital applications serving various administrations, questions arise for example on which budget to draw from or which department is responsible for the maintenance.

By setting up living labs – deploying smart city applications in a delimited area – and involving all of the city’s public service departments, the transformation process that leads to the comprehensive transversal management of smart city infrastructure can start.

With these projects, cities effectively support openness, verify interoperability, acquire knowledge and set the basis for public policies that address their local challenges and opportunities pragmatically while respecting their identity.

Read more opinions on challenges & opportunities brought by smart lighting here.

(

(