The virtues of contemporary light festivals

Tim Edensor, researcher of cultural geography at Manchester Metropolitan University (UK), and author of the book From Light to Dark: Daylight, Illumination, and Gloom, talked light festivals with Cities & Lighting magazine.

Light has long been deployed to enchant spectators. In the 17th and 18th centuries, European monarchs bedazzled subjects with lavish displays of fireworks, while illuminated pleasure gardens and theatrical lighting enchanted early modern cities. More recently, technological developments in illumination have encouraged a worldwide proliferation of light festivals that diverge in scale, length of duration, purpose and form.

In contending that light festivals are occasions for great creative, political and social potential, I identify four key qualities by drawing on examples of specific illuminations that were installed at various light festivals that I have visited over the past ten years.

- Firstly, I discuss how festive light installations can thoroughly defamiliarise the spaces to which we are socially and perceptually accustomed;

- Secondly, I focus on how particular light displays can enhance a sense of place;

- Thirdly, I look at how lighting techniques can promote lively forms of interactivity;

- Fourthly, I examine how festivals offer unique opportunities for professionals to experiment, share ideas and develop skills.

Defamiliarisation

Contemporary light festivals offer opportunities for practicing, representing and apprehending place in ways at variance to habitual experience.

Illumination possesses a rich capacity to make familiar places seem strange, altering the ways in which they are usually perceived. For instance, digital mapping techniques allow software to map out points on the structures of buildings. In addition to transforming the colours and textures of buildings, light projections that emerge from this mapping provide illusions whereby elements in the built environment appear to crumble, float, melt, evaporate or move.

Such dramatic effects can disrupt how we usually sense and understand a building while also revealing its distinctive architectural qualities, as evidenced by a succession of illusory effects designed by Marie-Jeanne Gauthé for her light projection, Jouons Avec Le Temps (Playing with Time), first staged at Lyon’s 2009 Fête des Lumières, and an early example of such approaches.

The ordinary might be made peculiar via illumination in other inventive ways. An example is Benedetto Bufalino and Benoit Deseille’s transformation of a traditional British red public telephone box into a glowing Aquarium, its interior lit from within to produce a brilliant blue scene of live fishes and green plants.

Originally featured at Lyon’s Fête des Lumières, the installation worked especially well in its ‘natural habitat’ in the UK at the Lumiere Durham festival 2013, where it was transformed from an ordinary fixture of everyday public space into a fantastical and uncanny object. The designers also suggest that a feature that was in the process of becoming obsolete might not be disposed of but reused in creative ways.

Inventive festive illumination such as the examples above can convert familiar local settings and fixtures into dream-like, mythical and fluid spaces, producing amusement and pleasure while also critically demonstrating that there are multiple perspectives through which we can sense our everyday worlds. By revealing the specificity of human modes of perception, this opens the city up to alternative interpretations and sensations, encouraging us to see the world otherwise.

Place-making

Besides defamiliarising familiar places, festive light installations can also contribute to place-making and enhance a sense of belonging. Such practices may be part of city-branding strategies but also underpin a sense of local belonging for inhabitants, causing them to reflect upon their everyday surroundings in new ways. They may powerfully conjure references to history, to celebrated events or to episodes from the past that have been overlooked.

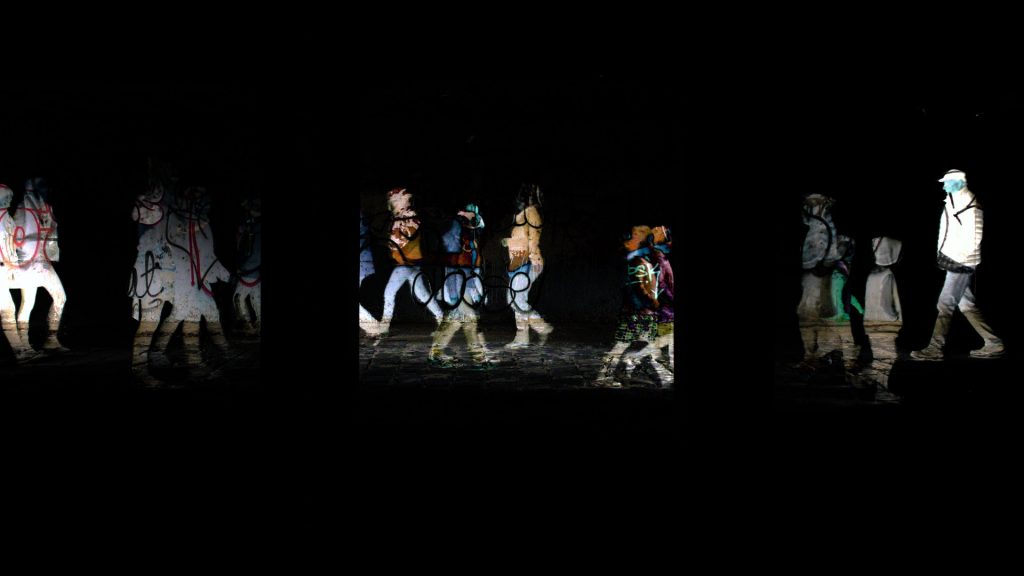

One example of the former is the 2014 festival that celebrated the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, attracting huge crowds to sample a range of illuminated attractions. Designers Christopher and Marc Bauder created a site-specific Lichtgrenze (a ‘border of light’) composed of 8000 white, illuminated rubber balloons atop poles that followed the 15 km path of the Wall. Simultaneously, historic film footage was projected on screens at points along the way, and after two nights, each helium-filled balloon was released in a synchronised sequence, symbolising the wall’s obsolescence and the objects and unvisited spaces.

Interactivity: fostering conviviality

A key role of much festive illumination is that it invites interactivity and public engagement, soliciting conviviality and playfulness in nocturnal settings that are usually quiet after nightfall. Large light festivals can certainly encourage communal playful participation but here I focus on smaller events.

Smaller light festivals often generate social inclusion, community participation, network building and the reaffirming of bonds. A host of newly formed, small-scale lantern parades has also extended the range of light festivals in recent years.

One such event is the biennial Moonraking Festival that takes place in the town of Slaithwaite, Yorkshire, held on a February evening. The festival is based on an elaborate 19th century legend about local men outwitting the police and involves a parade of lanterns devised according to specific themes, with the constant figure of a large moon-lantern at the head of the procession. The townsfolk produce a scene of vernacular surrealism, with a bobbing sea of oddly formed lanterns.

The procession forges a collective identity in familiar space, with bands adding to this playful occupation of usually quiet streets, as key features in the local landscape – canals, bridges and churches – are illuminated. A dark underpass is briefly illuminated by the parade and walkers sing and shout in this echoing realm. Bystanders line the road or lean out from the windows of adjacent houses, cheering and waving to marchers.

Moonraking thus encourages a festive conviviality manufactured by local people themselves, and crucially, the glow of lanterns sensually and affectively contributes to this potent atmosphere.

The fostering of interactivity through the deployment of illumination can create atmospheres of shared conviviality, silliness and playfulness in less local, intimate contexts, as exemplified at Sydney’s 2014 VIVID Festival, an event that prioritises the multitude of ways in which people can interact with light. Having made its debut in 2008 at Nevada’s Burning Man Festival and subsequently been installed at many light festivals across the world, The Pool, devised by Jen Lewin Studio, possessed over a hundred circular pads onto which visitors leaped, producing a burst of colour, the intensity of which varied according to the impact and weight of their landing. On busy nights, the scene was of a multi-generational, jumping throng of people who collectively generated dynamic patterns of colour to produce a swirling scene of bodies and light.

Light festivals as creative hubs

Finally, light festivals are occasions during which professionals congregate to share ideas, techniques and know-how. Arts administrators and managers, cultural entrepreneurs, artists, engineers, technicians and designers come together to forge new links, associations and communities of interest, typically in environments that are inclusive and open-minded. They are therefore arenas of cultural creativity in which prototypes emerge, a testing ground in which experimental concepts and new smart lighting techniques are developed and tested in situ. In fostering opportunities for new networks of association to emerge, Sydney’s VIVID festival, for one, has served as a testing ground in which experimental concepts and new smart lighting techniques can be tried out.

Light festivals have multiplied over the past 20 years. Over this time, the sheer diversity of innovative festive installations is extraordinary. It might be supposed that fatigue would have set in by now, with artists and designers running out of ideas and energy, but this is far from the case. Light festivals remain occasions during which a plethora of aesthetic, artistic and technical innovations in creative illumination proliferate, continuing to delight, challenge and energise spectators and participants.

An edited version of this article originally appeared in Cities & Lighting magazine (Issue #8, March 2019).

Tim Edensor teaches Cultural Geography at Manchester Metropolitan University and is a Visiting Scholar at Melbourne University. He has written extensively on national identity, tourism, ruins mobilities and currently, urban materialities. He has recently been writing about geographies of illumination and darkness, including festivals of light.

- Flip through Cities & Lighting magazine n°8 focusing on light festivals

- See more festivals in the LUCI Light Festival Calendar

- More about light, art and culture

Images © T. Edensor; Lichtgrenze, photo © Ralph Larmann; Bendigo Enlighten Projection Festival photo courtesy of Julie Andrews;